The High Performance Ecosystem: Part 3 A Pathway to Inspire & Develop

- Marc Portus

- May 28, 2019

- 8 min read

Updated: Oct 1, 2024

Marc Portus* and Derek Panchuk**

* Praxis Performance Group

This week, in part 3 of the HP ecosystem series, we look at high performance pathways. The pathway is an aspect of modern sport that is often talked about, but rarely defined. When we conduct our HP workshops, there are often differences people envisage when they discuss high performance pathways. For now we define it as:

The developmental journey, or pipeline, that connects junior and community sport to elite levels, and the systems and processes in place to support that journey.

The aspect we’d like to emphasise here is the journey. As people learn, mature, and develop at different rates this experience will be different for each participant and, for a sport to have a sustainable pathway, it needs to cater for these differences. This is one of the big challenges faced by sport in a competitive marketplace - the pathway is the opportunity for athletes to either move to more serious levels of the sport or as a more recreational pursuit. Sports need to be able to cater for all types of athletes. A fundamental concept when designing and working in pathway sport is to avoid the ‘conveyor belt assumption’, whereby, if athletes make a junior high-performance squad at a young age, then they are set for success in that sport for as long as they like. In reality it rarely works that way and many sports offering high performance under 12 squads or younger, rarely see many of those young athlete’s make-up high performance squads 5 or 10 years later.

The demographics of a sport play a role in how the high-performance pathway may look. Sports with high participation numbers, for example, in Australia, football (soccer), swimming, tennis, netball, cricket and Australian rules football, will identify their talent in a more ‘organic’ fashion than the niche sports. By this we mean athletes within larger sports are more exposed to the opportunities and the sport has more of a captured audience as it’s talent pool. Supply and demand for talented athletes is more easily met. Niche sports, with smaller participant numbers, need to be creative about how they identify and develop their talent. The concept of talent transfer has gained some notoriety in different parts of the world over the years for these types of sports, which we discuss in the next section. In a study of badminton performance pathways in Spain, Denmark, Indonesia and South Korea three basic pathway models for talent identification and development were proposed by North et al. (2016), which appears in Figure 1.

The process of talent identification and development through a sports pathway program can be done poorly or well, and it seems that many have not done it very well – see this commentary on football academies in England for a brief critique. Evaluating a pathway development program through a clinical return on investment model (i.e., turning young athletes into home-grown superstars) often leads to problems and the ones that suffer are the athletes, and eventually the sport will too. An alternative is to evaluate a pathway program by assessing holistic outcomes of the athletes themselves, such has skill progression, mental well-being, psychological skills, dual career/study progression, quality of interpersonal skills and relationships. Include performances, but don’t make performances the focus, they are part of the holistic picture. If all the other aspects mentioned above aren’t doing well, chances are the athlete will struggle anyway and performances won’t be sustained.

Finding the next superstar

At some point, you’re going to need to figure out which athletes are going to compete on the highest stage at the international or professional levels. Talent identification is by no means an exact science – a recent review by Roberts and colleagues (2019) has highlighted just a few of the issues associated with trying to identify athletes who will go on to be champions. Talent is a multidimensional construct and to distill it down to singular measurements is next to impossible – which again, demonstrates why having a strong pool of participants is so valuable.

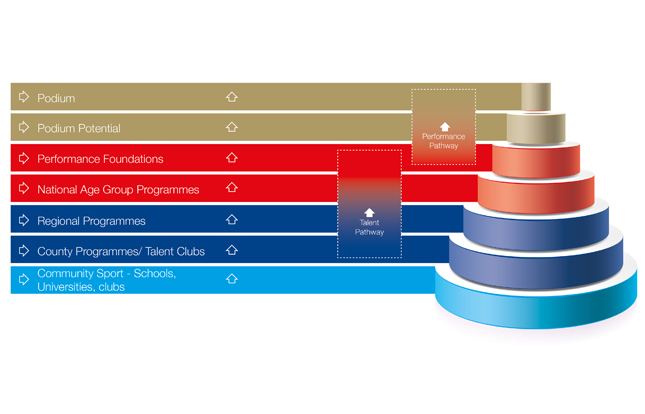

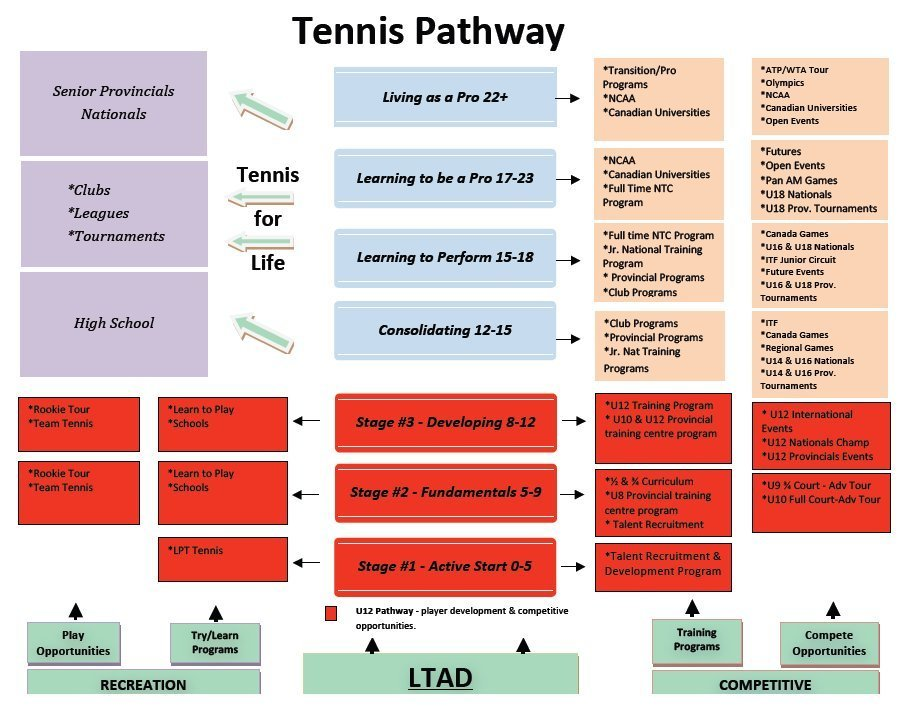

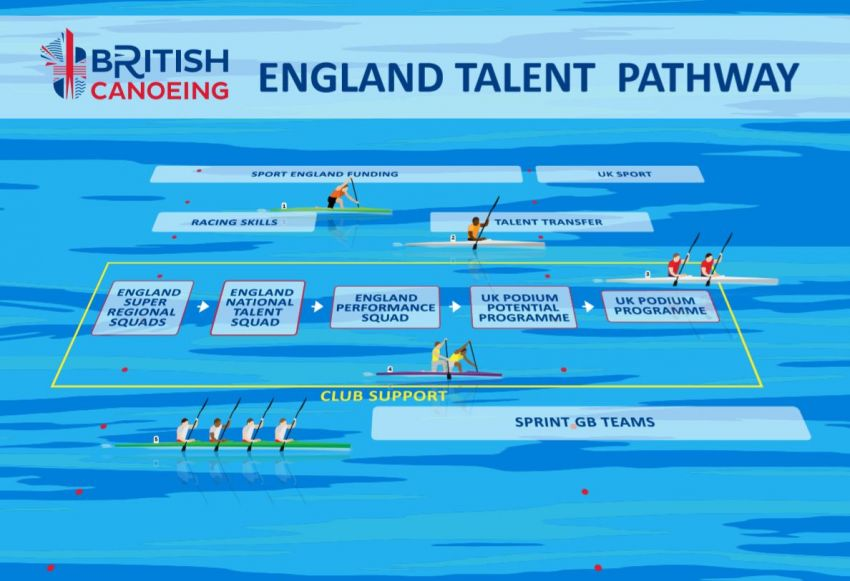

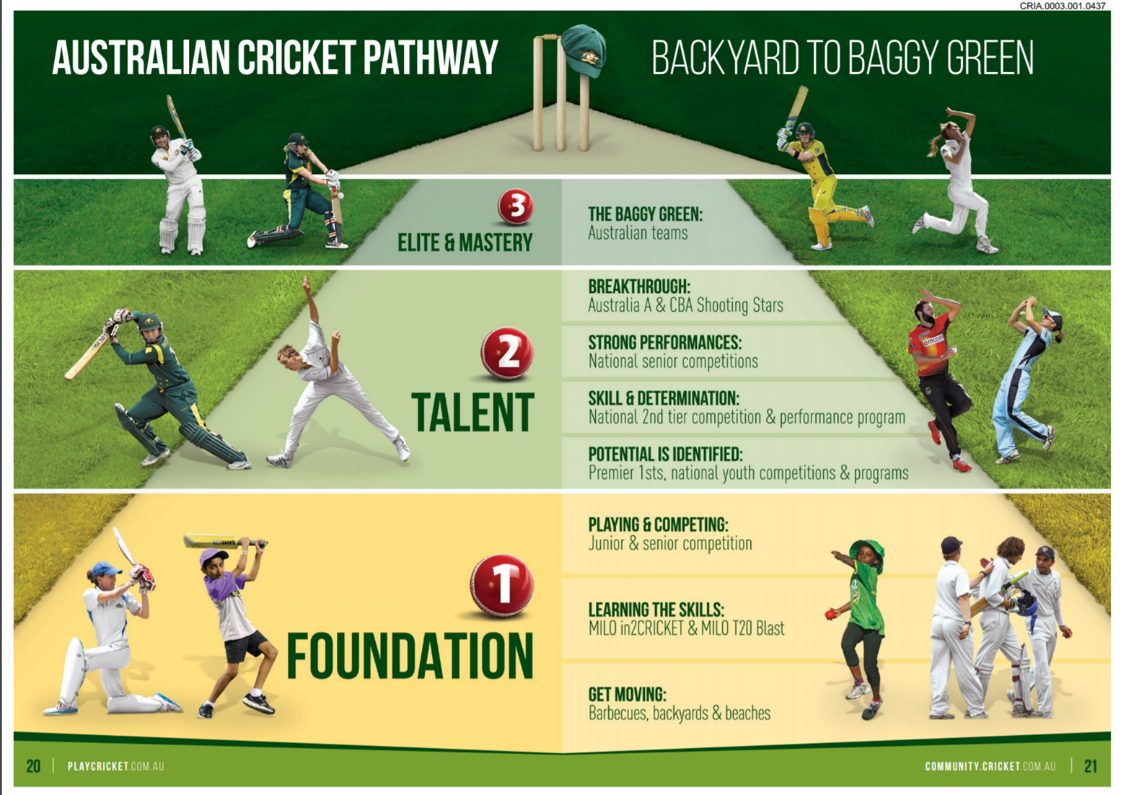

What’s the secret then? While there are no silver bullets, creating a good developmental framework is important. Most nations have adopted a framework to underpin their talent pathways; in Australia, the FTEM (Foundation, Talent, Identification, Mastery) framework is almost universally adopted while other countries have gone in other directions (e.g., Canada uses the LTAD (Long-Term Athlete Development) model) – see figure 2 above. In most cases, the framework allows you to overlay the developmental pathway and what’s required to support development at each stage. For example Softball Australia, has identified what mechanisms need to be in place across a range of dimensions to support athletes development. This can help articulate what sort of resources you need to support development as well as the sort of characteristics athletes should be displaying. Within the FTEM model it is the T1 – T4 phases where much of the important aspects of talent being recognised, confirmed over a period of time and further developed through dedicated training and competition that should form the backbone of a sport’s high performance pathway. The FTEM or LTAD models don’t need to be replicated verbatim in a sports pathway (something that seems to happen often in Australia, perhaps worryingly this is an indication of a lazy tick-box approach?), but the principles underpinning them should be understood and feature in a sports pathway design. Some examples of pathway models from UK Sport, Tennis Canada, British Canoeing and Cricket Australia are shown in the clickable slideshow below.

The actual process of talent selection is fraught with issues. To avoid selecting athletes that don’t belong and missing out on those that do, it’s important to rely on multiple perspectives and sources. Physical characteristics and capabilities only tell part of the story; you need to tap into the cognitive and behavioural aspects of performance as well. Coaches also possess strong instincts about the ‘x-factors’ (e.g., heart, desire, 'coach-ability', etc.) that athletes display to set them apart. Tapping into their expertise and combining it with objective measures can be valuable as part of a comprehensive talent identification and selection process. Finally, it’s important that athletes are given multiple opportunities to enter the elite space – there is no shortage of stories about late bloomers who were cut by their high school team and went on to star in their sport. It’s also important not to see the pathway as series of squad selections and competition experiences. These things are important but too often sports haven’t got the resources to do more, or don’t see the value of doing more. It takes time and effort, yes, but for a long-term, sustainable pathway that produces high quality, well-rounded athletes all the other factors mentioned above – dual career progression, interpersonal skills, quality relationships, support structures, psychological skills and optimum lifestyle management are all important ingredients for high performance sport pathways and initiatives. Materials, support and expertise need to be provided to athletes in the pathway in all these areas.

Domestic competition structures

Another often overlooked aspect of athlete development is the structure of the sport at national or domestic levels. These domestic structures in many cases are the foundation for international athletes to continue competing and refining their skills when there is no international competition. Ideally these competitions have an optimum size where there is a large enough elite talent pool to create ‘bench depth’ for the national team(s) and have enough capacity to introduce new developing talent to compete against the mastery level talent. It keeps everyone on their toes striving for continuous improvement and provides a terrific competitive nursery for international teams. Historically a noted strength of Australian cricket globally has been its domestic state competition 'The Sheffield Shield', or its variants. It contains a pool of approximately 150 professionally contracted players each year who battle it out for state champion honours and selection in the Australian cricket squad of approximately 25 -30 elite contracts. Its an interesting set of numbers which we don't suggest is the magic formula but perhaps food for thought for sports to assess their domestic competitions and what role they play in the HP ecosystem.

Talent transfer – the panacea?

In a competitive marketplace, like Australia, there are a multitude of sports and recreational activities vying for people’s time. The reality is sports with a relatively small participant base will need to supplement their performance pathway through initiatives such as talent transfer. Talent transfer refers to applying the skills developed in one sport into another where there are similarities or connections between the two that are important for success. Talent transfer can occur at various stages, from young athletes in their late teens through to ‘old stagers’ at the end of their career in their first sport. Classic examples are gymnasts moving to diving or freestyle skiing, or a female surf-life saving beach sprinter moving across to the Australian skeleton team for the 2006 Winter Olympics.

Many countries around the world now have transfer initiatives, often being conducted through government funded institutes of sport. You can read about a collection of athlete’s perceptions of these programs in this research from England here - it wasn’t that rewarding for some evidently. One notorious issue is a disconnect between the people managing the initiative – often a government funded institute of sport – and the sports involved themselves. Too often the athletes fall into a chasm of assumptions or overlooked management coordination between all the bodies involved, with some athletes exiting being totally disenfranchised by the whole experience (see the comments of athletes on pages 57-58 in the English example here if interested). An example of a well-planned talent transfer initiative is Gymnastics Australia’s Spin to Win program where GA has partnered with Ski and Snowboard Australia, Diving Australia and the Olympic Winter Institute of Australia to maximise the acrobatic skills developed in Gymnastics for the benefit of the other sports. You can check out the Spin to Win website here. If any reader has any experience of this program, please let us know in the comments section at the end of this article.

Developing Expertise

Its worth finishing by discussing what has been shown to contribute to the development of expertise in masters of their discipline. Anders Ericsson and colleagues probably produced the most discussed piece of work in this space when they analysed expert musicians, chess players and sports people in the early 1990’s. Their estimated years of deliberate practice was a minimum of 10 years, sometimes translated to 10,000 hours. Unfortunately, the findings have been popularised to mythical proportions and this is proposed as the 'magic number' needed to be an expert. Most masters of their field do end up specialising and have a strong history of dedicated intense high quality practice/training, whilst not being excessive to cause burnout. The trick is knowing the right time to specialise and the individual needs of the athlete and the context of their sport. Ideally its as late as possible to ensure a broad experiential base but without compromising the development of mastery in the eventual chosen area. In most sports, professional life-spans are short, so it can’t be too late. Think late adolescence as a starting point and work out the individual athlete – sport scenario from there.

So that wraps it up for this week. Feel free to login and provide some comments in the below, we’re happy to receive other views and comments.

If you would like to receive a weekly email when the last 2 parts of this HP Ecosystem series are published, please sign up at the top of this page or here. Next week is part 4 – the daily training environment.

Till next week,

Marc and Derek.

Want to know how to optimise your daily training environment? Or understand how to harness technology to get the most out of your athletes? Chiron Performance can help you find solutions to embed the science of skill acquisition and player development into your team or organisation.